What is to be Won

Walter Sebastian Adler

Background …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2

Literature Review…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3

ANALYSIS……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6

POLICY RECOMENDATIONS…………………………………………………………………………………….8

501(c)3 Adjacent Organizations……………………………………………………………………………………..8

Membership……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………9

Direct Benefits……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………10

Worker Skills, Education, Business development………………………………………………………………10

501(c)4 Political Action…………………………………………………………………………………………………11

Legislative Objectives…………………………………………………………………………………………………….12

Consolidate Public & Private Sector………………………………………………………………………12

One Union per Industry……………………………………………………………………………………………..13

Sectoral Bargaining……………………………………………………………………………………………………….14

Comprehensive Campaigns…………………………………………………………………………………….15

Theories of Change……………………………………………………………………………………………………….17

Implementation…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18

Implications…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..19

Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….20

Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….21

Cases Cited…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..24

Background

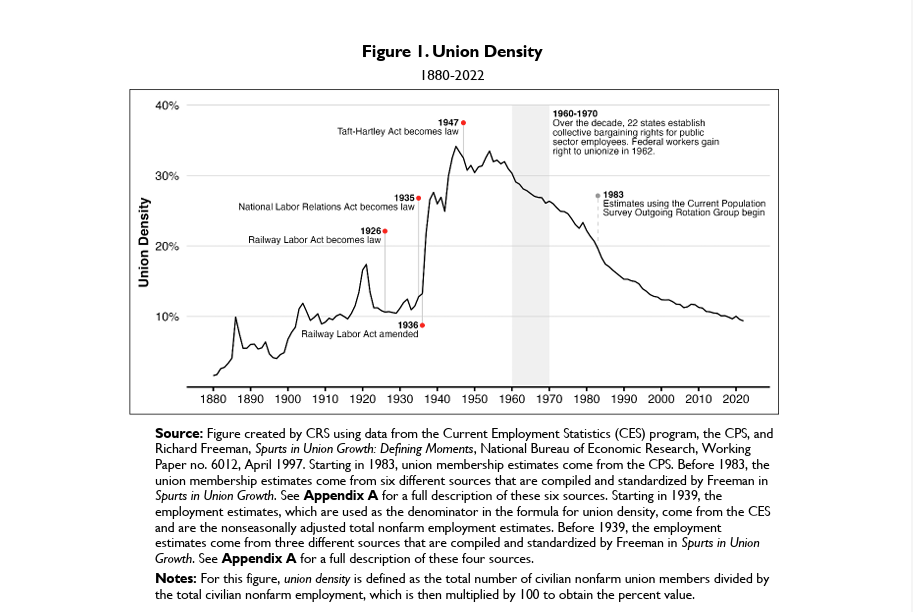

Despite renewed interest in unionization efforts at companies like Starbucks and Amazon, organized labor remains in total decline. Fewer than 9% of American workers hold union membership, and public perception of unions remains mixed at best, with many associating them with “corruption, inefficiency, and entitlement”. Right-to-work laws in 26 states, along with severe restrictions on public-sector strikes and bargaining in 39 states, further suppress labor power. While union-busting legislation, hyper-individualism, and globalization have all played a role, unions themselves have struggled to modernize and remain relevant to today’s workforce. Strict financial and legal constraints on 501(c)(5) trade unions hinder their ability to effectively mobilize workers, adapt new strategies, and expand their influence.

The average full-time American worker earns $1,192.001 per week. A modest income considering the high costs of living, taxes which consume 10-24% of one’s earnings2, and the decline of employer-provided benefits like 401(K) matching, paid sick leave, paid family care, subsidized healthcare, and perpetuity pensions3. This directly corresponds with the globalization of manufacturing and production to the lowest wages and most unregulated working conditions overseas, i.e. “the race to the bottom”. There is also a buffering of the classes in the form of an ill-defined “Middle Class”, an aspirational “Managerial-Professional Class”, and a robust regressive welfare state. Income inequality in the USA is and remains radical4.

However, the most definitive set of nails in the coffin of organzied labor is the National Labor Relations Act (hereafter NLRA) itself. It is in the very nature of this law and its amendments to slow down labor militancy, neuter the righteous rage of the working class, and drown unfair labor practices in the bathtub of legalese. In short, a system of lethargy by design; the NLRB exists in past and present form to limit tactics available for workers to leverage our power. One might track the decline of union density from the very passage of the Taft Hartley Amendments5 to the NLRA in 1947.

Around 91% of American workers are at-will employees, meaning they can be dismissed without cause, pursuant to employment law norms. Millions of undocumented, incarcerated, and literal slave laborers (sex work and agriculture largely) exist outside any substantive labor law protections6. Not well covered under the NLRA, should they even navigate how to engage with it. Many are in highly exploitative invisible servitudes. The dominant ideology, (i.e. neoliberal or conservative brand free market capitalism) suggests “unions are outdated”, and “unions are inefficient”. With only 9% of U.S. workers unionized7. One might see unions as either “ineffective”, “flawed” or perhaps “casualties of a deliberate campaign to turn back hard-won labor rights”.

Consquently, the World Bank thinks around 50% of the workers on earth work for under $5.50 per day. Many “union jobs” have been outsourced to nations that break strikes at gun point and have no actual rule of law. Or fully authoritarian states where workers will do what they are told, when they are told.

Literature Review

The highly flawed, structural issues baked within the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) extend beyond the Taft-Hartley amendments, reinforcing deep worker divisions (“The National Labor Relations Board: A Critical Evaluation” by Michael C. Harper). Most American workers do not identify as part of a “Working Class” but instead as individuals, who “by their own merits” navigate a labor market aspiring to an imagined middle-class status. Banerjee et al., Unions Are Not Only Good for Workers remind us that in many categories of civics, wages, and well-being: union density directly correlates to gains for all working people.

The most impactful legal defeat in recent years was Janus v. AFSCME, 585 U.S. 878 (2018), forcing all public employees to individually consent to union membership/dues check off. In Starbucks Corporation v. McKinney, No. 23-367 the U.S. Supreme Court imposed a stricter standard on the NLRB when seeking preliminary injunctions, potentially making it more challenging for the agency to obtain immediate relief against employers accused of unfair labor practices during union organizing efforts. There are “right-to-work” laws currently in 26 states (Benjamin I. Sachs, “Compulsory Unionism” and Its Critics: The National Right to Work Committee, Teacher Unions, and the Defeat of Labor Law Reform in 1978, Pacific Historical Review 81 (2009).), The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) operates with frustrating inefficiency (The NLRB’s Dysfunctional Role in Protecting Workers” by Richard B. Freeman), failing to penalize unfair labor practices (Failing Workers: The National Labor Relations Board and the Decline of Union Power” by Charlie Moret), failing to protect workers engaged in collective action, or empower them toward substantive mutual aid and protection (see The Decline of the National Labor Relations Board and Its Impact on Workers’ Rights” by Anne Marie Lofaso). NLRB decisions swing wildly based on political appointments (“The Labor Board: Politics and Policies of the National Labor Relations Board” by William B. Gould IV), creating an unpredictable landscape for labor rights. Board agents often display ideological bias or act as bureaucratic functionaries rather than neutral enforcers of the law.

There are no punitive damages for ULPs (NLRB v. Fansteel Metallurgical Corp. (1939). Republic Steel Corp. v. NLRB, 311 U.S. 7 (1940), NLRB v. Gullett Gin Co., 340 U.S. 361 (1951), Therefore, there are also few incentives besides credible threat of strike, slow down, or deep public shaming/ negative publicity to deter employer abuses (see Seth D. Harris et al., Modern Labor Law in the Private and Public Sectors: Cases and Materials (3d ed. 2021) at 415-426), also see Jane McAlevey, A Collective Bargain: Unions, Organizing, and the Fight for Democracy (Ecco 2020).

Additionally, restrictive definitions of who qualifies as an “employee” limit organizing potential (Cynthia L. Estlund, The Ossification of American Labor Law (2002)), see NLRB v. United Insurance Co. of America, 390 U.S. 254 (1968), Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co. v. Darden, 503 U.S. 318 (1992), see SuperShuttle DFW, Inc., 367 NLRB No. 75 (2019) while dividing workers by trade and sector—especially between private and public employment—benefits only those in power (Stephen Lerner, Three Steps to Reorganizing and Rebuilding the Labor Movement: Building New Strength and Unity for All Working Families, LABOR NOTES (Dec. 2002)).

For oligarchs, corporations, and their policymakers, “industrial peace” is synonymous with suppressing labor activism while maintaining high consumption and tax revenue cycles, repression and corporate activism against organzied labor is as American as apple pie, see Rosemary Feurer & Chad Pearson, eds., Against Labor: How U.S. Employers Organized to Defeat Union Activism (Univ. of Ill. Press 2017). Policy considerations should be drawn from an understanding of the basis of the sector division, i.e. how workers are fundamentally compensated; the public tax base vs. Private capital X on Public/ Private sector unions found in. The differences are rooted mostly in labor law jurisdictions, employment classifications, the basis of tax allocation. There are valuable theories of worker centered organizing that can read in Eric Blanc. We Are the Union, (2023). Ruth Milkman & Kim Voss eds., Rebuilding Labor: Organizing and Organizers in the New Union Movement (Cornell Univ. Press 2004). Importantly No Shortcuts: Organizing For Power In The New Gilded Age by Jane F. Mcalevey. These emphasize social movement unionism, organizing the most vulnerable, and the embrace of comprehensive campaigns. David Madland, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, emphasizes the role of sectoral bargaining in achieving a more equitable economy. In his book Re-Union, he advocates for a labor system that includes enhanced rights for workers and greater sectoral bargaining to complement workplace-level negotiations.

Studies exploring the importance of Sectoral bargaining, see Kate Andrias, Union Rights for All: Toward Sectoral Bargaining in the United States, in The Cambridge Handbook of U.S. Labor Law: Reviving American Labor for a Twenty-First Century Economy (Richard Bales & Charlotte Garden eds., Cambridge Univ. Press 2020). Important bargaining ideas in general are found in Jane F. McAlevey & Abby Lawlor, Rules to Win By: Power and Participation in Union Negotiations (Oxford Univ. Press 2023).

There are also several important international organizations one must be familiar with to see the viability of some these proposed policies; which when taken as whole transform more normative 501(c)5 labor unions into something more hybrid, more durable, and more akin to a “multi-structure-social movement” than a mere bargaining agent, or stale, visionless business union. Specifically, we draw your attention to the unique messaging styles, organizing methods, and social service provision structures of the Industrial Workers of the Word (hereafter IWW)8, the “New General Workers Federation” (hereafter HISTADRUT9), BRAC10, and 1199SEIU Healthcare Workers East (hereafter 1199). An overview of 1199SEIU organizing can be found in Upheaval in the Quiet Zone by Leon Fink & Brian Greenberg. This presents a durable best practice modal of an industrial union in the health sector. Its success links concepts of wall-to-wall industrial organizing, successful lobbying, social movement mobilization. The primary concept drawn from the IWW, is the prototypical idea of one big union (revolutionary industrial unionism), eliminating artificial divides of the working class, in rapid rise and rapid fall, see We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World by Melvyn Dubofsky and The Industrial Workers of the World: Its First 100 Years: 1905 Through 2005 by Thompson and Bekken. Compared and contrasted to Histadrut, which is arguably the only union to ever form a state, see Zeev Sternhell, The Founding Myths of Israel: Nationalism, Socialism, and the Making of the Jewish State (David Maisel trans., Princeton Univ. Press 1998), also see Adam M. Howard, Sewing the Fabric of Statehood: Garment Unions, American Labor, and the Establishment of the State of Israel (ILR Press 2017), and Jonathan Preminger, Labor in Israel: Beyond Nationalism and Neoliberalism (Cornell Univ. Press 2017).

A synopsis of BRACs economic ideas can be read in Freedom From Want: The Remarkable Success Story of BRAC, the Global Grassroots Organization That’s Winning the Fight Against Poverty, by Ian Smillie. BRAC is an organization that is simultaneously engaged in mass organizing, development, microfinance, education, and social enterprise. It is not a trade union at all, but instead the world’s largest NGO offering highly diverse social services.

Analysis

The solution to attrition, NLRB adjudication delay, ideological oscillation, anti-union legislation, and corporate refusal to bargain in good faith is to mount cost effective, worker driven comprehensive campaigns.

Trade unions today face existential challenges in retention, engagement, mobilization, and worker consciousness. Many workers no longer see unions as instruments for societal change or even as effective negotiators for better wages and benefits. Many blue-collar jobs have been moved overseas where the wages drop exponentially, and labor laws are worth the papers they are printed on. A large portion of the U.S. sentiment, particularly in the South, see unions in a far more negative light; “gangsters and communists”. Structural changes and bold visionary reimagining can reverse this trend. A worker always wins by affiliating with a union11 so why are we where we are? This fundamental question shapes the future of organized labor in the Americas. What can the individual worker gain and what clear victories can be collectively won to reset an imbalance which it rooted in our laws and codified in class? Union membership is in rapid decline. Unions must evolve to survive.

To increase our political and public influence, unions should establish 501(c)(3) organizations for hardship relief and public advocacy, as well as 501(c)(4) lobbying arms that reduce dependence on professional lobbyists. Trade-specific councils overlapping with other unions can enhance coordination, while involvement in these auxiliary structures should be incentivized. More aggressive tactics—such as graduated slowdowns, strikes, and public pressure—should be used earlier in negotiations, tailored to employer behavior. Unions must also support worker-owned businesses, offer direct services like childcare and legal aid, and prioritize retaining membership through job transitions. Consolidation of weak locals or underperforming entities should be pursued to build stronger, more effective unions across entire industries. Through a stratagem of “backwards and forwards linkages” unions must not only organize “wall to wall”, and on an industrial basis, but we must also organize in relation to adjacent industry, adjacent sector, and across supply chains.

This policy paper proposes critical reforms to strengthen union structures and organizational strategies. Comprehensive campaigns are usually massively expensive; this paper proposes how to reduce those costs. Unions should unify public and private sector locals within the same trades to foster collective action, pattern bargaining, and mutual aid. Organizing should expand across adjacent industries using off-duty union members paid per diem, reducing reliance on full-time staff organizers. Membership should be opened to per diem and undocumented workers, with separate units and training pathways to integrate them into union-covered jobs. Union membership should extend beyond current employment status, creating tiered systems of affiliation and solidarity.

To revitalize trade unionism, labor organizations must overcome not only external opposition but also internal atrophy(cite). As important as not being divided by sector is an understanding that each workforce, if not workplace, has a distinct culture. There must be clear shifts to defeat sector divides, as well as a unique voice and vision cultivated by very different terms and conditions in each workplace. Without a shift in approach, one that fosters greater engagement, broader worker solidarity (inter-union, inter-sector), and a clear vision for labor’s role in modern society, unions invite oblivion in an economy fully tilted toward corporate power.

“In order to recruit new members on a scale that would be required to significantly rebuild union power, unions must fundamentally alter their internal organizational practices. This means creating more organizer positions on the staff; developing programs to teach current members how to handle the tasks involved in resolving shop-floor grievances; and building programs that train members to participate fully in the work of external organizing. Such a reorientation entails redefining the very meaning of union membership from a relatively passive stance toward one of continuous active engagement.” Ruth Milkman & Kim Voss eds., Rebuilding Labor: Organizing and Organizers in the New Union Movement (Cornell Univ. Press 2004).

With no credible threat, the employing class acts with utter impunity. American trade unions, which in 2025 represent less than 10% of the work force, face serious existential challenges. With most American workers actually existing in the “Lower Middle Class”, lacking true job security, decent benefits, and legal protections, the need for strong, organized labor is more urgent than ever. The failure of labor laws and enforcement agencies like the NLRB to protect workers only underscores the importance of revitalized union activism and solidarity across sectors. Despite decades of attacks through legislation, ideology, and corporate pressure, unions are beginning to stir again, with organizing efforts at companies like Starbucks and Amazon signaling a renewed fighting spirit. To reclaim their power, unions must reconnect with workers’ daily realities, build cross-sector unity, and offer a compelling vision for economic justice and workplace democracy.

This policy paper suggests essential shifts in structures and organizing frameworks. Though each of these are subject to exhaustive research and discourse, this paper will focus on five key policy recommendations related to legal structures and campaign strategies. The importance of Public-Private Sector unity in collective action and the development of allied-aligned c-structure entities to achieve a wider range of tactics and worker engagement, being the recommendations of greatest importance.

Policy Recommendations

(1) Unions should set up 501(c)3 Adjacent Organizations for worker hardship, increase appeals to public sympathy, engage the press more effectively and circumvent NLRA bans on secondary activity. 501(c)3 entities are tax deductible, grant eligible, and can perform a wide range of charitable activities, peer support, and hardship grant making. There are specific tight caps on what they can spend on either lobbying, or direct labor organizing. They cannot endorse candidates or take partisan positions.

The union has to facilitate the start-up of these new entities and has to have a framework for supporting them without dominating them, which is hard and runs counter to human nature. Legally speaking the union CAN fully control the c3 if its officers do not, and even its officers can hold board positions except for those of treasurer and president. The 501(c)5 thus, can develop the brand, bylaws, strategic vision AND can donate to the entity, but some clear conflict of interest procedures must be developed.

- Unique President/ Treasurer

- Separate Executive Officers

- Should be a public, private, third sector composed leadership

- Separate websites

- Separate bank accounts

- Caps on how much political or labor activity spending can occur

Primary benefits: operation of tax-free social services, accessing grant money, developing positive soft power from hardship support, capable of giving tax deductible incentives for contributions that a UNION 501(c)5 CANNOT. This can be tent for confidence building between multiple unions exploring a merger. Now you can manage strike funds/ lay off funds in more sophisticated financial manner then a 501(c)5 can. You can circumvent bans on secondary activity during labor impasse. You can operate social services for members and non-union members of the industry you wish to organize as a gateway to union membership. You can absorb non-citizens with less scrutiny than a regular union can.

- Membership should not be limited to “employees”. Unions should deliberately represent workers not inherently covered under the Act, per diem workers specifically and undocumented workers generally, organized into separate units12.

In 1954 Union membership in the USA peaked at around 35% of the available labor force13 As said, the NLRA is not on the side of the working class. The price of industrial peace is always worker rights attrition.

Using the structures outlined we should invite any worker, any person, citizen or not, who will pay dues or show willingness to be trained and find work to become a “member”. Membership should not be based purely on being employed at a union site, nor should one have to wait to “be certified” by the NLRB to be a member. Nor should dues be the only way to achieve membership. We should make it easier to join, and easier to stay when you leave your union employment. If this cannot be properly executed vie the c5 it can certainly be worked out in the c3 and c4. Under the NLRA, several categories of workers are not considered employees and are therefore excluded from its protections14. There should not be an aristocracy of labor, there should not be arbitrary divisions. Nationalism is anathema to class struggle.

This is a humanitarian imperative, but it is also a strategic issue of representing those that other elements of organized labor have ignored. Working people, which when develop a consciousness of their class and situation; recognize they do in fact share a shared relationship of subservience and alienation as Karl Marx said. They share a common experience of dependency on the employing class to have organized the capital, structures, and circumstances that make their employment, their ability to feed their families possible. Now, to what degree socialists tell us this antagonism need result in revolutionary violence, is perhaps a matter of just looking at the last 100 years, but from the perspective of a conscious worker: they trade their time and labor fora wage, that is generally disproportionate to the profits the employer earns but having organized the venture. But sewing class hatreds has not born practical fruit. The violence revolutionaries tend to unleash has thus so far installed authoritarian factions in power with little regard for human life, much less workers’ rights, human rights, any rights. The real lesson of the last 100 years of struggle between the parties of the working class and various kings, aristocrats, robber barons, churches, states and capitalists is that once you begin killing people, it is often hard to stop. I personally do think we wish to live under Russian or Chinese rule, societies shaped in every single way by the unleashed “worker state”.

The humanitarian imperative of the labor movement is not based on revolutionary violence or “utopian schemes”. None of those schemes have borne fruit in 100 years as they played out in almost every nation on earth. The objective of a union, a democratic union, is to provide a structure for concerted activity, for mutual aid and protection, on behalf of the working class. It is our imperative to take in workers, who individually are vulnerable and isolated, lacking agency, lacking choices. It is our job to train and empower them to be able to harness collective power for action.

We should develop a means to train these workers in skills/credentials needed at union work sites. Union membership should not be wholly contingent on employment at a union job; there should be other tiers/ types of membership. We want lifetime union membership; we want entire families enrolled. We want union membership to take on a new significance and pride. We cannot complete with nationalism or religion, but we should try since neither of those two will act in tangible solidarity, in the way a democratic union can.

(B) Unions should provide more direct benefits, such as hiring halls, training, childcare, and legal services and develop more mechanisms to retain worker membership when they resign or are terminated.

The power to bargain collectively will never be as powerful as the ability to provide actual services to one’s members. This is where hybrid entities such as HISTADRUT and BRAC come into our analysis. Neither are pure labor organizations. Arguably, HISTADRUT is the largest trade union in Israel and BRAC the largest NGO on earth. Both began with similar ideas about poverty alleviation through mass movements, both have long proclaimed commitments to workers empowerment, human rights, and social justice. Today, BRAC is one of the largest employers and social service providers in Bangladesh and (16 other nations), HISTADRUT is the largest union in Israel. Whatever you may think of their actual politics; both are veritable tool kits to see what types of services can be organzied at the c3 or c5 level to win hearts and minds.

The “gangster” union trope is the Teamster tough guy who demands the boss pay for your kids’ school or twists the arm with a strike until the boss pays you; but it is still the boss paying and the gangster making threats. Here, HISTADRUT and BRAC saw that power is derived not only by threat, or credible threat; it is derived by what organization can provide for human needs while fighting for human wants. HISTADRUT, in the name of labor Zionism/ social democracy AND BRAC in the name of emancipatory development/human rights literally formed banks, land funds, universities, medical services, micro-credit, agricultural cooperatives, small business developments, and BOTH, albeit HISTADRUT in a colonizing venture, and BRAC in a humanitarian international development mode; they build non-state infrastructure frankly unheard of by any non-state entity. Today, whatever you man think of the Israeli occupation in Palestine, or the fragility of Bangladesh and its rampant poverty; I ask you look beyond the rhetoric and the politics and see the methodology.

Using the 501c3-cahritable foundation, c4-advocate lobby, c5-union architecture what I am advocating is to develop unions from being about collective bargaining inside a NLRA framework we will never properly win, because it is a loaded dive game set up by lawyers for workers to fail. Instead, we look at the tool kits, the architecture of emancipatory development well established by HISTADRUT, BRAC: a union begin to develop our own networks of social services, so we have one less think to wrench out of the greedy claws of the employing class; we as union, or confederation of unions begin providing the kinds of services that in the past had to be begged from employer wages, or state largesse.

(C) Unions should enable worker education, entrepreneurship and small business development.

All the groups listed (except for the IWW, which barely exists today in skeletal nostalgic form) possess varying funds and scholarships for workers and children of workers to gain important skills and education. But there is not much thought or planning on how to retain them in the loyal orbit of the movement once they gain the agency to become “upper middle class.”

With NYSNA Nurses (NPs) making over 170K and an IAFF Firefighter who after his 22-year pension begins at age 42 opens a hardware store chain and now makes 440K; are these people still in the actual working class? Do they retain any incentive to pay union dues and support the organization that benefited them while they worked for others?

1199 of has a robust hiring hall and worker training system, it also has varying schemes to keep one’s health benefits and pension between different employers.

BRAC and HISTADRUT both understand that not every worker wishes to work for someone else forever, and absorbing all types of talent back into the organization has staffing limits. 1199 is good at identifying leadership talent in delegates and promoting them to organizers and VPs. But BRAC/ HISTADRUT both fully understand some of the limitations, if not all of the limitations of collectivization and socialist ideal. Some people wish only for good jobs and safe conditions, a pension on which to retire, and others have entrepreneurial spirit that the union should not lose to Managerial-Professional Class. Thus, it should be noted that BRAC and HISTADRUT make microloans, and business loans to their members and beneficiaries. It would be better to develop a humane and ethical small-medium business class from workers than wish to work for themselves, then hemorrhage educated people from one’s movement, or have them as ally, where not most unions will lose them when they graduate.

It is highly advantageous strategically for a 501(c)3 to partner with a 501(c)4. They can emanate from the same council the public/private union convenes; they must have unique presidents, treasurers, website, bank accounts from the c5, and each other. The practical implication is to train workers in more sophisticated modes of “mutual aid and protection”, as well as to provide the nucleus of social service support systems union should offer not contingent on employer contribution.

(2) Unions should set up 501(c)4 Lobby organizations for greater political impact and rely less on paid lobbyists. Such entities can mobilize worker votes, engage in effective lobbying for budget allocations and industry wide protections.

It is far more effective to mobilize the votes of your workers into a local block in municipal elections and primaries, than to rely only on professional lobbyists to lobby. The worker storytelling, the worker as constituent, is highly effective, and also costs less. The practical implication is to train workers to have political understanding, mobilized for voter turnout. This apparatus can also augment all manner of public visibility. This is the entity that can:

- Accommodate the political action objective of multiple allied unions

- Lobby with no caps on finances

- Set up SuperPAC funds

- Mobilize voters in blocs

- Develop legislation that benefits the union membership

- Can absorb members, non-citizens, per diems, and non-NLRA bound category of workers that are not directly employed at a unionized workplace

What we are in essence doing is developing a practical framework to merge common trade industrial unions, clubs, or associations into one allied entity (a super-union) through practical cooperation.

A Joint Council specific to logical groups of trades and those community interests they impact at the very least involving a public sector union, a private sector union, and community-based organizations as appropriate.

A Public Advocacy Council 501(c)3– mobilizing hardship help for workers of a type of field/trade/industrial grouping of labor no matter what sector which makes appeals to the public for varying work grievance or bargaining goal decided upon.

A Political Action Committee 501(c)4– mobilizing worker votes within a type of field/trade/industry no matter what sector.

Both types of entities can also absorb third sector workers. The most modest example of this methodology is Local 501(c)5 representing primarily public-school teachers and Local 501(c)5 representing private school teachers; form a joint council which sets up 10 to 20 overlapping bargaining goals. This is their Collective Bargaining Objectives (of both sectors). They then agree to fund and staff a 501(c)3 for charitable help to teachers and encouraging public respect and support of education; then a 501(c)4 to encourage local politicians to help fund and support their industry. There are now 4 types of organization aligned behind the CBO goals; and both the c3, and c4 can provide support for both new organizing into the 2 union. As importantly any of the 4 entities can provide membership and benefits to the third sector worker without that worker being an employee under the NLRA, a local State code, or even a citizen.

The ultimate goals of this confidence building are to unify wall to wall, i.e. all the workers in the institutes of the primary trade; in a stacked public/private c5, and joint c3 charity and c4 lobby serving the whole allied work force.

The initial goals of the lobbying division are to:

- Help our friends, get our opponents and neutrals out of office.

- Educate workers on which politicians support their interests.

- Rank local politicians on responsiveness to workers issues.

- Mobilize union voters.

- Make local elected officials responsive to labor related issues.

The specific macro goals of the lobbying division are to:

- Run pro-worker candidates in primaries.

- Draft and pass laws that protect workers rights.

- Increase the enforcement of workers rights/protections on the state level.

- Repeal Taft Hartley.

- Repeal anti-union/ union avoidance State laws

- Expand the NLRA to all classifications of workers.

- Reform the NLRB to be efficient in processing charges and claims.

- Enact powers of punitive damages for ULPs.

(3) Unions should consolidate public and private sector unions of the same class of trades into unified associations for collective action, pattern bargaining, and mutual aid.

There is no U.S. Supreme Court ruling that directly authorizes or prohibits the merger of public and private sector unions. However, federal law, specifically the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), does not bar unions from representing both groups. Public-sector labor relations are governed by state laws, which can vary widely—some states may impose restrictions, while others allow broader union representation. In practice, several major unions represent both sectors, such as SEIU, AFSCME, and UFCW. These unions operate across legal boundaries by ensuring they follow distinct rules for each sector. While such arrangements are legally possible, unions must carefully manage different bargaining rights and regulatory frameworks to remain compliant.

The NLRA applies as said to the majority of the private sector. State labor laws apply to the public sector. Varying Federal and State health, safety, employment regulations apply to all sectors, citizen worker or undocumented worker alike. It is obviously harder to figure out much of that safety net as an at least hidden undocumented worker, and when exploited you have no real substantive remedies (Kate Andrias, Union Rights for All). Incarcerated workers have almost no rights to speak of. Actual Slavery, though banned under the 13th amendment, remains quite intact. But almost everyone pays taxes of some form.

The only actual difference between a public, private, or third sector worker is by what revenue stream their employer is compensating them for their work. Work is therefore an ecosystem. Public-sector labor relations are primarily governed by state laws, which can vary significantly. Some states may have restrictions or specific requirements for public-sector unions, affecting their ability to merge with or be represented by unions that also represent private-sector workers, see.

Private sector workers are taxed alongside public sector workers, but public sector workers are compensated with those tax dollars, which in theory support essential public services that allow for capital and enterprise to thrive. We have almost 500 years of proof we cannot allow the employing class to run unchecked. We have almost 100 years of proof that eliminating the private sector and consolidating the economy under a single party, one public sector state is regressive, violent, unfree, and also very bad economics.

There is a general sense that certain services are “essential”, to be funded by the tax base and provided by career civil servants; such as police, fire, sanitation, education, utilities, and public hospitals. The same forces that decimated the American labor movement, push a regime of privatization; the further fissure of the work force; lobbying for state sub-contracting of essential services to private firms. It is in the public sector where a far larger percentage of workers are unionized (32.2%-per Dept. Of Labor). Public sector jobs, in general, are more stable, less competitive, offer more benefits, and pay generally lower wages than the private sector. Most private sector workers are “employees” under the NLRA (excluding several million persons)15, while most public sector workers are “employees” under a state labor code (Modern Labor Law at 89).

Here, the fundamental issue is formation of durable alliance of confidence building and mutual aid between the relevant labor unions of the private and public sector. Where 90% of the country is non-union; in general, this is about the public sector union forming a partnership or salting and seeding16.

(4) There should only be one union per industry and the aim of that union is sectoral bargaining.

Sectoral bargaining needs to be the order of the day17. The public and private unions of a particular industry must work harmoniously and then seek to merge. These council need to be accessible, on and offline, they need to develop strategic alliances with non-unions; i.e. all the stakeholders that an industry affects. These councils should not before symbolic co-endorsement and back-patting, echo chambers, they should be to seed and salt the entirety of an industry.

We are wasting a lot of time trying to pry individual contracts out of the hands of each separate employer (Cemex Construction Materials Pacific, LLC, cited as 372 NLRB No. 130 (2023). Unions should set up all industry specific councils that overlap with other unions and encourage/ incentivize membership on 501c committees to increase involvement. But the goal has to be a merger, we do not need or want competing worker organizations that can make separate deals with management and be pitted against each other.

We must map and chart all existing Canadian, American, Carribean, and Mexican organzied labor by three classifications: private sector, public sector, and a third sector (all those not covered under the NLRA, or a local state labor code thus needing special protection to be outlined). Once mapped-charted; it will be clearer if there are overlapping industries which hold both a private and public work force, and if relevant who represents them currently. Those fields with discernible public/private competition or at least dual provision of services should be focused on. The intuitive next step is the “seeding” of a structure which can allow for the coordination of both founding unions’ goals, codified in a joint program, i.e. collective bargain objectives. Meeting all three sectors unique conditions/ arrangements/deployment of work, having to do with divergences in employment funding modal.

Again; the tax base (public), private capital (private), and a wide swath of vulnerable fields (domestic work, sex work, agriculture, undocumented trades ect.) which are sometimes public funded, largely private funded, often in an informal economy but always exploited (Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. v. NLRB, 535 U.S. 137 (2002)).

“Unions often focus on easy targets and hot shops, organizing workers in various sectors unrelated to their core industry. To offset membership losses, they expand into areas like public service, healthcare, and manufacturing. However, this generalist approach weakens their effectiveness, as they struggle to make significant changes in industries where they represent only a small portion of workers. This masks the growing weakness in their core sectors,” see Lerner, Three Steps to Reorganizing and Rebuilding the Labor Movement at 7.)

Unions should seek consolidation of entire industries via merger of existing entities or actively raiding locals that make no demonstrable gains for their workers.

There should not be multiple amalgamated locals, these entities are an embarrassment and at best are incompetent. At worst connected to organzied crime. Eliminating non-credible corner store locals is always a strategic imperative.

To effectively organize and empower millions of workers, the labor movement must consolidate into a smaller number of large, sector-based unions, (see Lerner, Three Steps to Reorganizing and Rebuilding the Labor Movement at 5). The current structure of 66 fragmented and overlapping unions hinders coordinated growth. While many union leaders seek survival by diversifying into multiple industries, this strategy often weakens worker power. Instead, labor must reorganize into unified, well-resourced sectoral unions that are strategically focused on winning gains for workers in their industries. These unions should collaborate within a stronger federation that sets collective strategies and ensures accountability in carrying them out.

(5) All future organizing requires the deliberate use of COMPREHENSIVE CAMPAIGNS. All future organizing must involve and be led by actual workers.

A Comprehensive Campaign is an advanced labor organizing strategy that goes beyond traditional methods by incorporating research, community coalition-building, media publicity, political and regulatory engagement, and both economic and legal pressure. These multifaceted efforts aim to strengthen collective bargaining or unionization efforts by mobilizing support from a wide range of allies and leveraging multiple pressure points on employers. Though rooted in the U.S. where unions face fewer legal protections and cultural support than in Europe comprehensive campaigns are becoming increasingly relevant globally, as employers adopt American-style union-avoidance tactics. While these campaigns remain relatively rare in the U.S. due to their high cost and complexity, more unions are investing in the capacity to deploy them, viewing comprehensive strategies as essential to adapting to the evolving global labor environment (Bronfenbrenner & Hickey, Winning is Possible: Successful Union Organizing in the United States, 24 Multinational Monitor 6 (2003);

The core elements are:

1) Adequate and Appropriate staff and financial resources;

2) Strategic Targeting;

3) Active and Representative rank-and-file organizing committees;

4) Active Participation of member volunteer organizers;

5) Person-to-Person contact inside and outside the workplace;

6) Benchmarks and Assessments to monitor union support and set thresholds for moving ahead with the campaign;

7) an Emphasis on Issues which Resonate in the workplace and in the community;

8) Creative, escalating internal pressure tactics involving members in the workplace;

9) Creative, escalating external pressure tactics involving members outside the workplace, locally, nationally, and/or internationally; and

10) Building for the first contract during the organizing campaign

“Backwards and Forwards Linkage” in BRAC’s jargon; is the ownership of different units of production, supply, and retail throughout a supply chain. For our policy organizing purposes this means unionizing up and down a supply chain. Which necessitates the consolidation of unions by industry, and consolidation of the public and private sector into one labor union, albeit with separate bargaining & legal divisions; as the NLRA and State Labor Codes do not contain the same processes.

The base is your own industry (private and public sectors of it)

- There should only be ONE UNION PER INDUSTRY

- Followed by whatever other classifications of employee work in the bargaining units when defined

- Followed by non-union shops of the same type of industry

The secondary target sets are the next 2-3 adjacent industries

Such as warehouse workers to truckers to longshoreman to sailors. Such as hospital nurses to EMS to nursing homes staff to medical supply companies to pharmacies. The tertiary target sets are individual workers of unskilled, semi-skilled trades that are aided by the union in filling vacancies at bargain unit sites or send to school for skilled/ semi-skilled training to fill in a unionized job site of need. Unions should organize adjacent industries18 using workers not employed at those specific job sites; paid organizer staff should be greatly increased19, with a far greater utilization of off duty union members/delegates paid per diems for short engagements. Unionized workers should be paid per diem to engage with workers of the same industry and different plants/bases/companies. Using workers to organize fellow workers is far more effective than the use of paid organizers alone. To achieve a cost-effective comprehensive campaign a union will need to have consolidated, set up a council for the industry to enlist additional coalition partners. And developed its c3/c4 capability. Efforts like that require a COMPREHENSIVE CAMPAIGN. Which requires much higher levels of planning.

Here, this fundamentally means wall to wall + adjacent industry organizing. Which is well accepted in principle, but not well actualized. Low hanging fruit organizing, i.e. units under 25-50 workers has been seen without any result in Starbucks (site). Insert number of stores brought under joint employer farmwork. Because there are continued limitations on union organizers entering work sites, see Lechmere, Inc. v. NLRB, 502 U.S. 527 (1992), see Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, 141 S. Ct. 2063 (2021).

An obvious paranoia and active retaliation against the key/lead organizers of a campaign who are employees, the suggestion is to use union employees (on volunteer or per diem basis) to organize workers of same type.

Organizing Departments should be expanded, and more money should be spent on utilizing more sophisticated modes, which means hiring more expertise driven staff, but at the core of the comprehensive campaign is the involvement of the lay worker, and volunteerism has hard limits with the working class. So, organizing departments should develop systems of hour pay so workers can be used effectively as front-line communicators of the benefits of unionization. There is a time and a place for the quintessential “wiley-socialist wobbly”, there is a place for the “honed labor maven”, but the starring role in a comprehensive campaign is the fellow worker of your same field, extolling the benefits of industrial democracy as well as explains the nuts and bolts. Explaining their “feelings about the union” is more important than sharp comms propaganda, tight scripted catch phrases, and rhetoric. That is because the working class recognizes their own, and each work force does have a unique style and jargon. There is a place still for a professional organizer. There is room for mavens. But to see women and men of your own trade, class, and profession explain what the “union feels like”; that is akin as to why story telling is far more effective tool than power points.

Unions should be prepared to engage in public pressure, economic pressure, slowdowns, work to code, and strikes sooner in the bargaining cycle and deploy more aggressive economic tactics than mere pickets early on, perhaps prior to any negotiations. These tactics should also be pattern escalation tactics proportional to company bad faith, surface bargaining, and ULPS.

It is highly stressed that the elements of a comprehensive campaign are in place to allow full utilization of all necessary tactics of secondary activity, launched from the structures of the c3 and c4.

THEORIES OF CHANGE

- ONE UNION PER INDUSTRY

- SECTORIAL BARGAINING PREFFERED

- FALSE NECESSITY- rejection of left/right, liberal/conservative, loaded historical jargon. Reject any affiliation with any party. There are compatible liberal and conservative approaches to social policy (Oberto Ungar).

- REJECT THE PRIMACY AND IMPORTANCE OF THE NLRA/ NLRB PROCESS

- DEMOCRATIC CONFEDERALISM

- Actual use, empowerment, and training in civics and democracy

- Human Rights Oriented

- Actual commitment to Democracy, democratic autonomy

- Always drawing leadership from the rank and file

- Councils for trades, councils for sectors, council for industries

- Worker led, worker mobilized industrial democracy

- ADVOCACY VIA WORKERS POWER: Workers educated, trained, and empowered to lead their unions.

- Always pro-worker

- Always organize the most vulnerable workers

- QUOTA DIVERSITY– not fake liberal DEI, quota driven balance of identities in all levels of the organization

- SOLIDARITY: IMPROVE CULTURE/ MORALE/ SURVIVAL/RETENTION VIA “MUTUAL AID AND PROTECTION”- Hardship Help with seeding 501c3s.

- ADVOCACY/ORGANZING/INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY- 1 strong union per industry.

- COMPREHENSIVE CAMPAIGN– low to no budget comprehensive campaigns using the joint council, using the c3, c4, c5 stack.

- BACKWARDS AND FORWARDS LINKAGE IN ORGANZING

- LEGISLATIVE CHANGE– lobbying essential funding/ increased scope

- One code of law for all workers

- EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT/ ELEVATION– hiring halls and skill building

- CREDIBLE THREAT DOCTRINE

- Always prepared for a strike, boycott, or action.

- Always ready to strike in the first 3 months of bargaining first contract.

- Always ready to escalate.

- Always able to mobilize secondary activity via the affiliated groups on the joint council

- Ready to mobilize the private sector in strike when the public sector isn’t legally allowed to

- FOSTER PUBLIC SYMPATHY AND UNDERSTANDING– appealing to the public we serve to support us/ also via the press.

- WORKER SUPPLIED CONTENT ON ALLIED MEDIA– allowing workers to tell their own stories online, to each other, to the public, to increase our trade visibility.

- ALWAYS PRO-WORKER concerted activity, “organized for mutual and protection”, and engaged in what can only be described as “the most low-budget/cost-effective/ democratic comprehensive campaigns in history.

- Actual readiness to put workers above union brands. Actual investment in the training of a union membership that values democratic participation, civic involvement, and feel real solidarity with fellow workers in other trades. Actual willingness to cooperate and consolidate unions, all a big if.

Implementation

Stage One:

SUPER–SEEDING– setting up hybrid public/private/community structures that allow for higher levels of worker support services, higher levels of political education/ legislative action, and set up the basics of a comprehensive campaign for the industry which can operate complete unrestricted by NLRA bans on secondary activity (NLRB v. Fruit & Vegetable Packers (Tree Fruits), 377 U.S. 58 (1964), National Woodwork Manufacturers Association v. NLRB, 386 U.S. 612 (1967), Longshoremen v. Allied International, Inc., 456 U.S. 212 (1982).

Stage Two:

SUPER–SALTING– organizing union members/organizers to not only take jobs in companies one plans to unionize, but also taking employment in varying 501c3/501c4 entities that the union wants to learn from or have interest in enlisting into the joint council. With a particular focus on infiltration and organization of agricultural workers, domestic workers, sex workers, and railway/airline workers.

Stage Three:

SUPER-UNIONS: one per industry representing the public and private sector of the industry with willingness to absorb and train NON-NLRA covered workers. This consolidation should attempt to be voluntary and democratic but should not hesitate to raid smaller amalgamated locals with histories of non-performance on behalf of their members.

Stage Four: PILOTS

Mounting a series of demonstration campaigns along critical industry supply lines. Such as public and private education; such as public and private healthcare; such as organizing in a traditionally non-union southern work force using the c3/c4 to lead into a c5. Such as training organizers to form c3, c4 units inside no NLRA covered work forces.

Stage Five: CAMPAIGNS

Replicating on a larger scale campaign with a focus on up to four adjacent industries aligned in one comprehensive campaign. Such as trucking/sanitation, farming/groceries, schools (public + private), and healthcare (public + private).

Implications

What are the pros and cons?

The main pro is that this is expected to greatly increase union density. It will make the unions more central to American life and increase the bargaining power we have via larger industrial unions leveraging industry wide concessions.

The main con is that it deeply changes the economics and power centers of a trade union taking on new costs and responsibilities, as well as workers who don’t have the same protections the NLRA offers bonified “employees”. We also run the risk of trading the 63+ national AFL CIO unions for 9 to 10 that are bloated bureaucracies that capitulate more readily to corporate interests. Alot of this policy also assumes that rank and file workers will make time and effort to adopt these structures, which are dominated at the present time by the Professional Managerial Class. It is also important to note that the radical IWW barely still exists 120 years after formation. The Histadrut was highly culpable in the displacement of Arab workers and likely has characteristics unique to a Jewish context. BRAC is far more like a mega NGO, and a bank than it is like a social movement. 1199SEIU has very unique advantage of being a healthcare union, which occupies a uniquely important place in the economy and imagination. So, none of the four groups have typical worker demographics/ dispositions in 2025. Anarchism and Socialism are fully marginal ideologies. Palestine is in literally amid war crimes and instability. Bangladesh is one of the poorest countries on earth and its going under water. You will see IWW members at punk rock concerts, but what contracts have they won lately? 1199SEIU is alone the closest local example and they have not taken any steps to consolidate their industry, or to engage the public sector. There are legal and structural reasons for this.

What is feasible?

For the AFL-CIO or SOC to sponsor a demonstration campaign using organizers and union members from the big four.

What are the predictable outcomes?

At the time of writing in 2025 there are 63 unions in the AFL-CIO. The best-case scenario initial outcome would be to get buy in from one large private sector union and one large public sector union to carry out a timebound, heavily monitored and evaluated comprehensive campaign pilot.

Such as a local of AFSCME and a local of SEIU partnering in an urban work force.

In general reference, we will want to identify the 4 largest American labor organizations20Which include the National Education Association (NEA), the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT); and the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), which represents public sector workers across various government agencies and services.

These unions are among the most influential in the U.S., with significant organizing power and political impact. Each has deeply entrenched interests and should all be expected to initially reject the totality of this policy plan. In the next 50 years most of the Teamsters will be replaced by robots. As will many roles in the SEIU. For the forceable future most, Americans will want human teachers, medical workers, and public servants.

Conclusion

The working class and the employing class have at least one thing very much in common, it is that neither has figured out how to exist without each other. Try as either side might, over the last 200 years it remains clear that worker self-management devolves into a highly unproductive blood bath, see all experiments with socialism, (Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes, The Black Book of Communism, Stéphane Courtois, et al), which all failed.

On the other hand, neither globalization nor automation have allowed the employing class to fully replace, outsource, or employ fully at will, i.e. restore widespread serfdom and slavery. Without democratic super-unions, without organized labor we would have children in mines, 80-hour weeks, and zero labor protections. Like much of the world actually still has if you consider it. Quite like what corporations seek out- when they move jobs abroad.

In the same thinking that a public and private sector worker have more in common with each other than with an employer, for ages Communists have asked the working class to have more in common with each other, than with the nation state, or sky-pie religion. That also largely has failed. The Union, as we today still understand the union, is dying out as it is not evolving in form and function. The working class is still highly vulnerable in most of the world. This paper does not ask for the Titanic to be raised and for seas to part; nor is it a love letter to defeated ideology. We ask what is left of the labor movement to take a chance on a demonstration campaigns and see if the juice is worth the squeeze.

We were once told we had nothing to lose buy our chains; then the chains developed in different forms, in differing contexts. The unions and labor laws of today are still a type of chain. We do not have to gamble our lives on ideas about things we have never seen proven; we should instead invest in proving ideas that we have seen partially work. The emancipation of the working class has nothing to do with bigger, better unions, better laws. It has everything to do with empowerment. If the working woman and man look to the union as provider, protector, and means for advancement the union itself is a means to win. If the union is an actual service provider, an employer, a political mobilizer, a party, one invests in what provides one actual meeting of needs, attainment of wants; and above all else: makes our lives and work have dignity.

Bibliography

Kate Andrias, Union Rights for All: Toward Sectoral Bargaining in the United States, in The Cambridge Handbook of U.S. Labor Law: Reviving American Labor for a Twenty-First Century Economy (Richard Bales & Charlotte Garden eds., Cambridge Univ. Press 2020).

Kate Andrias, Sectoral Bargaining in the United States, in The Cambridge Handbook of Labor and Democracy (Angela B. Cornell & Mark Barenberg eds., Cambridge Univ. Press 2022).

Asha Banerjee et al., Unions Are Not Only Good for Workers, They’re Good for Communities and for Democracy: High Unionization Levels Are Associated with Positive Outcomes Across Multiple Indicators of Economic, Personal, and Democratic Well-Being (Econ. Policy Inst. Dec. 15, 2021).

Eric Blanc, We Are the Union: How Worker-to-Worker Organizing Is Revitalizing Labor and Winning Big (2023).

Rami Ginat & Daniel Blatman, British Trade Unions, the Labour Party, and Israel’s Histadrut (Palgrave Macmillan 2021).

Kate Bronfenbrenner & Robert Hickey, Winning is Possible: Successful Union Organizing in the United States, 24 Multinational Monitor 6 (2003).

Paul F. Clark, John T. Delaney & Ann C. Frost eds., Collective Bargaining in the Private Sector (Cornell Univ. Press 2002).

City Univ. of New York Sch. of Labor & Urban Studies, The State of the Unions 2024 (2024), available at https://slu.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/The-State-of-the-Unions-2024.pdf.

Stéphane Courtois et al., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Jonathan Murphy trans., Harvard Univ. Press 1999).

Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (abridged ed., Univ. of Ill. Press 2000).

Leon Fink & Brian Greenberg, Upheaval in the Quiet Zone: 1199SEIU and the Politics of Health Care Unionism (2d ed. Univ. of Ill. Press 2009).

Rosemary Feurer & Chad Pearson, eds., Against Labor: How U.S. Employers Organized to Defeat Union Activism (Univ. of Ill. Press 2017).

Richard Freeman, Spurts in Union Growth: Defining Moments, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 6012, April 1997 (hereinafter, Spurts in Union Growth, 1997.)

Richard B. Freeman, The NLRB’s Dysfunctional Role in Protecting Workers, in The Labor Movement in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities (Columbia Univ. Press 2010).

Walter Galenson, Split Corporatism in Israel (SUNY Press 1992).

William B. Gould IV, The Labor Board: Politics and Policies of the National Labor Relations Board (Univ. of Cal. Press 1979).

William B. Gould IV, The Labor Board: Politics and Policies of the National Labor Relations Board (MIT Press 1985).

Michael C. Harper, The National Labor Relations Board: A Critical Evaluation, 36 Labor Law Journal 253 (1985).

Seth D. Harris et al., Modern Labor Law in the Private and Public Sectors: Cases and Materials (3d ed. 2021).

Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914–1991 (Vintage Books

1996).

Adam M. Howard, Sewing the Fabric of Statehood: Garment Unions, American Labor, and the Establishment of the State of Israel (ILR Press 2017).

Michael L. Katz, The National Labor Relations Board in the Trump Era: A Constitutional and Political Critique, 50 Industrial Relations Research Association 120 (2019).

Ian Kullgren, Infighting at Labor Board Paralyzes Its Operations, Politico (Apr. 18, 2018), https://www.politico.com/story/2018/04/18/national-labor-relations-board-infighting-529688.

Jamelle Bouie, This is What Happens When Workers Don’t Control Their Own Lives (December 14, 2021) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/14/opinion/tornadoes-mayfield-amazon.html

Samuel Kurland, Cooperative Palestine: The Story of Histadrut (Arco Publishing Co. 1947).

Stephen Lerner, Three Steps to Reorganizing and Rebuilding the Labor Movement: Building New Strength and Unity for All Working Families, LABOR NOTES (Dec. 2002), https://labornotes.org/2002/12/three-steps-reorganizing-and-rebuilding-labor-movement-building-new-strength-and-unity-all.

Anne Marie Lofaso, The Decline of the National Labor Relations Board and Its Impact on Workers’ Rights, 29 Workplace Rights Review 185 (2018).

Jonathan Preminger, Labor in Israel: Beyond Nationalism and Neoliberalism (Cornell Univ. Press 2017).

David Madland, Re-Union: How Bold Labor Reforms Can Repair, Revitalize, and Reunite the United States (ILR Press 2021).

Jane F. McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age (Oxford Univ. Press 2016).

Jane McAlevey, A Collective Bargain: Unions, Organizing, and the Fight for Democracy (Ecco 2020).

Jane F. McAlevey & Abby Lawlor, Rules to Win By: Power and Participation in Union Negotiations (Oxford Univ. Press 2023).

Ruth Milkman & Kim Voss eds., Rebuilding Labor: Organizing and Organizers in the New Union Movement (Cornell Univ. Press 2004).

Charlie Moret, Failing Workers: The National Labor Relations Board and the Decline of Union Power, 45 Labor Studies Journal 31 (2020).

Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Arthur Goldhammer trans., Belknap Press 2017).

Nicholas A. Pittner, Better Bargaining: Navigating the Minefield of Public Sector Collective Bargaining (Bookbaby 2021).

Benjamin I. Sachs, “Compulsory Unionism” and Its Critics: The National Right to Work Committee, Teacher Unions, and the Defeat of Labor Law Reform in 1978, 78 Pacific Historical Review 81 (2009).

Ian Smillie, Freedom from Want: The Remarkable Success Story of BRAC, the Global Grassroots Organization That’s Winning the Fight Against Poverty (Kumarian Press 2009).

Zeev Sternhell, The Founding Myths of Israel: Nationalism, Socialism, and the Making of the Jewish State (David Maisel trans., Princeton Univ. Press 1998).

Fred W. Thompson & Jon Bekken, The Industrial Workers of the World: Its First One Hundred Years: 1905 Through 2005 (Industrial Workers of the World 2006).

On Labor https://onlabor.org

Power at Work https://poweratwork.us/

Labor Notes https://www.labornotes.org/

CASES References

- NLRB v. Fansteel Metallurgical Corp., 306 U.S. 240 (1939)

- Republic Steel Corp. v. NLRB, 311 U.S. 7 (1940).

- NLRB v. Gullett Gin Co., 340 U.S. 361 (1951).

- NLRB v. United Insurance Co. of America, 390 U.S. 254 (1968)

- NLRB v. Fruit & Vegetable Packers (Tree Fruits), 377 U.S. 58 (1964)

- National Woodwork Manufacturers Association v. NLRB, 386 U.S. 612 (1967)

- Longshoremen v. Allied International, Inc., 456 U.S. 212 (1982)

- Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co. v. Darden, 503 U.S. 318 (1992)

- Lechmere, Inc. v. NLRB, 502 U.S. 527 (1992).

- Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. v. NLRB, 535 U.S. 137 (2002)

- Janus v. AFSCME, 585 U.S. 878 (2018)

- SuperShuttle DFW, Inc., 367 NLRB No. 75 (2019)

- Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, 141 S. Ct. 2063 (2021).

- Cemex Construction Materials Pacific, LLC, cited as 372 NLRB No. 130 (2023)

- Starbucks Corporation v. McKinney, No. 23-367 (2023)